The headquarters of Fanuc sit in the shadow of Mt. Fuji, on a sprawling, secluded campus of 22 windowless factories and dozens of office buildings. The grounds approach the lower slopes of Japan’s most famous peak, encircled by a dense forest that Fanuc’s founding CEO, Seiuemon Inaba, planted decades ago to shield the company’s operations from prying eyes—an example of the preoccupation with secrecy that once led Fortune to compare him to a bond villain.

Since taking over as chairman and chief executive officer in 2003, Inaba’s son, Yoshiharu, has continued the tradition of privacy. He takes questions from investors only twice a year, wearing a blazer in the lemon yellow the company uses to brand the factory automation robots it produces, the factories its robots work in, its employees’ uniforms, and the company cars that shuttle engineers and executives around the neighboring village of Oshino.

The elder Inaba once explained this uncharacteristically loud touch by calling yellow “the emperor’s color.” It also helps security guards quickly identify outsiders. In Seiuemon’s day, the fear was industrial espionage; today’s spies are more likely to be working for investors or stock analysts who want to peek behind the lemon curtain for insight into everything from global automobile manufacturing to iPhone orders.

On a warm afternoon in May, the company cars come and go like bees from a hive, ferrying visitors through the front gates near a towering green dormitory. Keisuke Fujii, who manages public relations for Fanuc Ltd., isn’t scheduled to meet me, having already offered the expected “no comment” on behalf of executives and the company. When I arrive unannounced at the security checkpoint, hoping to persuade him to do otherwise, he’s away from his office phone; a guard offers to escort me while I search the grounds for him.

We don’t find Fujii, so I leave the campus with little more than a glimpse of the world behind Inaba’s forest: a clock above the entrance to the main research facility that ticks at 10 times the usual speed, as if innovation can’t happen quickly enough for the world leader in factory automation technology, plus several 40,000-square-foot factories, each of which contains hundreds of bright yellow Fanuc robots working around the clock to build other Fanuc robots, stopping only when no storage space remains. Some robots will be shipped elsewhere in Japan, where strict immigration policies and a declining birthrate have left manufacturers of all sizes more dependent on factory automation. But most are bound for China.

Automation has been rising over the past decade there, partly because, as wages and living standards have risen, workers have proved less willing to perform dangerous, monotonous tasks, and partly because Chinese manufacturers are seeking the same efficiencies as their overseas counterparts. More and more, it’s Fanuc’s industrial robots that assemble and paint automobiles in China, construct complex motors, and make injection-molded parts and electrical components. At pharmaceutical companies, Fanuc’s sorting robots categorize and package pills. At food-packaging facilities, they slice, squirt, and wrap edibles.

King of them all is the Robodrill, which plays first violin in one of the great symphonies of modern production: machining the metal casing for Apple Inc.’s iPhones. In the fiscal year surrounding the 2010 introduction of the iPhone 4, the first to use an all-metal casing, Robodrill sales more than doubled.

Since then, this relationship has become so chummy that, based solely on strong first-quarter Robodrill sales, analysts discounted early rumors the iPhone 8 would eschew metal casing for front-and-back glass panels. Instead, the recent iPhone 8 release and coming iPhone X launch spurred higher Robodrill sales to Apple’s manufacturers in China, some of which are building new factories to assemble the company’s phones. New iPhones also mean more demand for Robodrills from Chinese smartphone makers such as Xiaomi, Vivo, Oppo Electronics, and Huawei Technologies, which often present their own more affordable models in the wake of each fresh offering from Apple.

And as China goes, so goes the rest of the industrial world. Multinationals that are reshoring operations from East Asia to North America and Europe are doing so in part because automation promises sophisticated production methods and labor savings; they, and companies who stayed out of China in the first place, are spending more than ever on industrial robots. The overarching pattern is less a reversal of the 20th century’s offshore manufacturing boom than an unraveling, with jobs vanishing from developing and developed nations alike.

Amid the tumult, there’s one clear winner: the $50 billion company that controls most of the world’s market for factory automation and industrial robotics. In fact, Fanuc might just be the single most important manufacturing company in the world right now, because everything Fanuc does is designed to make it part of what every other manufacturing company is doing.

In 1955, Fujitsu Ltd., the world’s third-oldest information technology company after International Business Machines Corp. and Hewlett-Packard Co., tapped Seiuemon Inaba, who was then a young engineer, to lead a new subsidiary dedicated to the field of numerical control. This nascent form of automation involved sending instructions encoded into punched or magnetic tape to motors that controlled the movement of tools, effectively creating programmable versions of the lathes, presses, and milling machines you might find in shop class.

From the beginning, Inaba spent heavily on research and development without concern for dividends—a corporate mission he described as “walking the narrow path.” But within three years, he and his team of 500 employees were shipping Fujitsu’s first numerical-control machine to Makino Milling Machine Co. In 1972, Fujitsu-Fanuc Ltd.—the “Fanuc” an acronym for Fuji Automatic Numerical Control—was founded as a separate entity, with Inaba in charge.

The next phase of global manufacturing, he believed, would be computer numerical control, which relied on a standard programming language. At the time, the 10 largest CNC companies in the world were based in the U.S., but within a few years Fanuc had overtaken them all. By 1981, almost solely because of Inaba’s innovations, more than 11,000 industrial robots were being used in Japanese manufacturing operations, helping streamline processes such as sheet-metal cutting and engine-part machining.

These were welcome advances for manufacturers in most developed economies, where employment costs had been rising steadily since the beginning of the 1970s. Even so, these early robots required enough human participation (and unions and labor laws were sometimes strong enough) that many industries ended up focusing more on increasing productivity than on slashing jobs and wages. That meant, for example, that machinists who worked more slowly than robots might instead become swift assemblers of finished parts.

The next step for Inaba was to take Fanuc’s CNC systems and make them networkable. With this frontier in mind, he built the Oshino headquarters and, in January 1981, while his new forest grew, invited media and industry leaders from around the world to come watch robots make parts for other robots. The factory he showcased was staffed by 100 human workers, each of whom did the work of five men, aided by NC machine tools and industrial robots that turned out parts which they then assembled.

The resulting press coverage caught the attention of Roger Smith, who had recently become president and CEO of General Motors Corp. Smith had joined GM’s accounting division 30 years earlier, after spending the final two years of World War II in the U.S. Navy. He’d risen through the corporate ranks slowly, gaining prominence as GM deftly navigated the gasoline crisis of the 1970s to become America’s top automaker.

When Smith took over, GM held 46 percent of the U.S. auto market, but the industry was in decline, and most companies were looking to cut costs and improve efficiency to compete with Japanese automakers. GM was in the enviable position of being flush with cash, and Smith had ideas, most of which sought to restore the company’s focus on technological innovation. Like Fanuc, GM had pioneered early developments in numerical control, including the use of a storage system to record the movements of a human machinist, then mimic them on demand. Such experiments had led Smith to imagine what he called a “lights-out factory of the future,” which would so limit reliance on assembly workers at GM plants that lights and air-conditioning would be unnecessary. The company failed to advance very far in that direction, though, choosing to focus instead on the traditional manufacturing methods that were helping it dominate the U.S. auto market.

Fanuc’s robots were unlike anything Smith had seen outside his own dreams, and he soon decided he’d found the way forward for GM. A year after he became CEO, on a humid June afternoon in Troy, Mich., a yellow robot bowed first to Smith and then Inaba before swinging its arm to cut the ribbon for a joint venture called GMFanuc Robotics Corp.

The partnership assured Fanuc a lucrative future with one of the world’s largest manufacturing companies, in the world’s biggest car market. But for Smith, the moment was tinged with regret. In meeting with his executives to sell them on the partnership, he hadn’t bothered to mask his feelings about the Japanese. “Never again can we let them take our technology and beat us at our own game,” he said, according to Steven Parissien’s history The Life of the Automobile.

With the deal struck, a staff of 70 workers in Japan set about developing GMFanuc’s first robots, which were bound for the $600 million Buick City complex in Flint, Mich. Smith suggested to the New York Times that their work could eventually expand beyond automobiles. “We may make the first electronic, automatic vacuum cleaner,” he said. “You walk out the door in the morning, and at 11 o’clock this thing comes out and vacuums the whole house while you’re gone.”

In 1986, after four years of development, the Buick City factory’s first industrial robots were unveiled. But as soon as they were put into service building GM cars, they proved problematic, even embarrassing. According to Parissien, the factory’s 260 industrial robots “frequently gave cockeyed instructions, ordering up the wrong bumpers, the wrong trim, the wrong welds, or the wrong paint, sending instructions to the next robot, which was too simple-minded to notice the errors. The paint robots were particularly cantankerous, slopping gobs of paint on one car, then not enough on the next.” More cantankerous still were robot arms meant to delicately attach windshields to Buick LeSabres, which instead would ram them inside the cars, forcing human workers to retrieve and set them by hand. Engineers strained their eyes trying to manage the endless lines of code necessary to keep the robots working in concert, and when the code needed to be updated, the factory’s 5,000 human workers would stand idly by.

Well before Silicon Valley adopted the mantra “fail fast, fail often,” Fanuc had observed its own version of the dictum, allowing Inaba to innovate through ambitious trial and error. But GM seemed to learn little from GMFanuc’s failures, never much improving the efficiency of its robot or human workforces. Jim Hall, a former GM executive, told Automotive News the problem hadn’t been Fanuc’s technology as much as how the American company had tried to use it. “GM saw that the average Japanese plant had so many robots, so GM thought more would be better,” Hall said. “They didn’t know how and why the robots were being used, they just wanted to use more of them.”

The sheer quantity of robots may have overwhelmed GM’s engineers, but it did wonders for Fanuc’s bottom line. The automaker spent tens of billions of dollars on the GMFanuc project, funding Inaba’s investments in the next iteration of Fanuc’s factory of the future. The Japanese company made huge technological strides in the first six years of the partnership, becoming in 1988 the world’s largest supplier of industrial robots.

Agreements between Fanuc and other manufacturing giants, such as General Electric Co., soon followed, but for GM’s investors, improvement wasn’t coming swiftly enough. Smith was additionally chastened by another money-losing initiative, the $7 billion GM-10 project, which had produced cars derided as overpriced and unimaginative. He took still more heat when he backed away from robotization and instead embraced offshoring, becoming the villain of Michael Moore’s 1989 documentary, Roger & Me, about 30,000 GM workers who’d been laid off in Michigan. Late on the morning of July 30, 1990, Smith drove off into retirement in the first car from the (non-GMFanuc) assembly line at the Saturn plant in Spring Hill, Tenn., with nine troubled years staring at him in the rearview mirror. GM’s share of the U.S. auto market had plunged from 46 percent to 35 percent during his tenure.

Fanuc made a final score from the U.S. automaker in 1993, when Smith’s successor, John Smith (no relation), sold GM’s share in the robotics venture back to Fanuc. After years of GM-funded innovation, the Japanese company had regained its independence and managed to keep its former partner as a customer. A decade later, as Yoshiharu was taking over from his father, the Japanese company fulfilled Roger Smith’s dream, opening a factory in Oshino where robots made other robots in the dark.

Earlier this year, during one of Fanuc’s rare open houses, Vice President Kenji Yamaguchi told investors that about 80 percent of the company’s assembly work is automated. “Only the wiring is done by engineers,” he said. And when you have lots of efficient robots making your other robots, you can sell those robots more cheaply—about $25,500 for a new Robodrill. (You can find a well-used older model on EBay for $8,500.) Volkswagen Group, for instance, pays about 10 percent less for Fanuc robots than it paid for ones it previously purchased from Kuka AG, a German company.

Fanuc manages to offer these savings while maintaining 40 percent operating profit margins, a success that Yamaguchi also traced to the company’s centralized production in Japan, which is made possible, even though most of its products are sold outside the country, by the 243 global service centers that keep its robots operational. The company even profits from its competitors’ sales, because more than half of all industrial robots are directed by its numerical-control software. Between the almost 4 million CNC systems and half-million or so industrial robots it has installed around the world, Fanuc has captured about one-quarter of the global market, making it the industry leader over competitors such as Yaskawa Motoman and ABB Robotics in Germany, each of which has about 300,000 industrial robots installed globally. Fanuc’s Robodrills now command an 80 percent share of the market for smartphone manufacturing robots.

In the first quarter of 2017, North American manufacturers spent $516 million on industrial robots, a 32 percent jump from the same period a year earlier. A study published by the Brookings Institution shows many of them are ending up in steel and auto manufacturing centers such as Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio. According to the report, there are about nine industrial robots for every 1,000 workers in Toledo and Detroit—three times the figure for 2010. Many of these robots are Fanuc’s. Its machines are also in Tesla Inc.’s Gigafactory, in Nevada, lifting heavy chassis and delicately assembling battery trays, among other tasks. Its sorting robots, meanwhile, are ubiquitous at Amazon.com Inc.’s massive warehousing and shipping facilities.

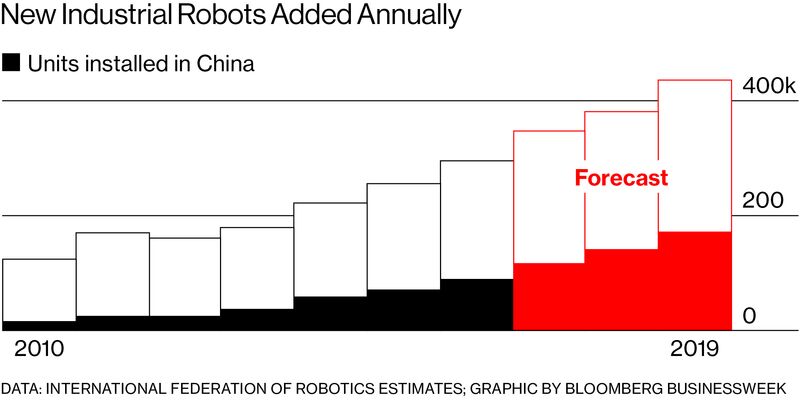

Orders from the U.S., though, are dwarfed by those from China—some 90,000 units, almost a third of the world’s total industrial robot orders last year. Sales to China amounted to about 55 percent of the $5 billion Fanuc’s automation unit generated in the fiscal year ended March 2017. The International Federation of Robotics estimates that, by 2019, China’s annual industrial robot orders will rise to 160,000 units, suggesting Fanuc will be insulated from any slowdown in the world’s second-largest economy. Yoshiharu told investors at his most recent Q&A session in April that the company expects demand in China to outstrip supply even after Fanuc opens a factory next August in Japan’s Ibaraki prefecture. The facility will be dedicated solely to keeping up with Chinese demand.

Research into the effects and possible consequences of widespread robotization has yet to clarify whether it will make life distressingly idle or wondrously drudge-free. In a study published earlier this year by the National Bureau of Economics Research, researchers from Boston University and MIT estimated that from 1990 to 2007 each new industrial robot displaced five human workers. A recent German study of the period from 1994 to 2014 put the figure at two workers but noted that unions and workers’ councils may have limited manufacturing job losses there and that medium-skilled workers’ wages were nevertheless depressed. (The same study found that Germany hadn’t experienced net job losses, because younger workers were entering other sectors.)

Automation in China, meanwhile, has yet to harm wages, and a recent report by Bloomberg Intelligence suggests the country’s medium-skilled workers are still seeing wage gains. Those workers’ fortunes are perhaps being buffered, for now at least, by electronics manufacturing. Song Wufong, a middleman in Shanghai who connects foreigners with small and midsize factories in provinces such as Fujian and Guangdong, says that workers in Shenzhen, Guangdong’s manufacturing hub, have so far been somewhat insulated from automation because electronics manufacturing still relies “on human hands that can perform very detailed tasks,” such as wiring and assembly.

But Song says this will change as industrial robots become smaller and more affordable. “Just a few years ago it was unusual to see a small or midsize factory using robots,” he says. “Now I see it more and more often as I travel around meeting with factory owners.” Song was born in the much poorer province of Jiangxi, just north of Fujian and Guangdong, where he worked for years doing unskilled factory labor. He made shoes, toys, and eventually auto parts. “I’m lucky I left when I did,” he says. “Every time I visit, I meet another friend who lost his job to a robot.”

This trend was confirmed by Hong Tao, director of operations at the Beijing office of Pinkerton Consulting & Investigations Inc. Hong says that when he joined the China wing of the world’s oldest international detective agency in 2001, the company mostly concerned itself with busting counterfeiters, investigating fraud and embezzlement, and providing security for foreign executives, with the odd kidnapping case mixed in. Then, around 2012, U.S. companies that once wanted his help opening factories began asking for help closing them down.

“When one of our clients closes a factory in China, it’s my job to prevent any violence or unrest by negotiating a severance package that the workers and the company can both live with,” Hong says over tea at Pinkerton’s Beijing office. This has become a growth industry for Pinkerton, as wages continue to rise and foreign manufacturers continue to flee. About one-third of the dozens of companies Hong has helped move their factories to Thailand or Vietnam, where labor is cheaper. “The rest of them,” he says, “are replacing Chinese peasants with Japanese robots.”

Toward the end of 2015, Fanuc joined a handful of other Japanese companies to invest a combined $20 million in Preferred Networks Inc., an artificial intelligence startup with 60 employees. The modest funding masked a hugely ambitious goal: becoming as dominant in manufacturing AI as Amazon and Google Inc. are in their fields, which Preferred Networks planned to do by partnering with Japanese manufacturers that generate immense troves of data.

The company’s co-founder and CEO, Toru Nishikawa, told the Financial Times that while visiting Fanuc’s factory, he’d noticed the absence of AI technology. He saw a chance to apply deep-learning techniques to data culled from Fanuc’s army of manufacturing robots throughout the world so they can improve their own capabilities. When robots make other robots ceaselessly, without human intervention, he said, “data can be collected infinitely.”

The result of Nishikawa’s insight was the Fanuc Intelligent Edge Link and Drive, or Field. The system, introduced in 2016, is an open, cloud-based platform that allows Fanuc to collect global manufacturing data in real time on a previously unimaginable scale and funnel it to self-teaching robots. According to Fanuc, Field has already yielded advancements for tasks such as robotic bin-picking. Previously, the selection of a single part from a bin full of similar parts arranged in random orientations required skilled programmers to “teach” the robots how to perform the task. Now, Fanuc’s robots are teaching themselves. “After 1,000 attempts, the robot has a success rate of 60%,” a company release said. “After 5,000 attempts it can already pick up 90% of all parts—without a single line of program code having to be written.”

Fanuc has so far declined to discuss its strategy concerning its venture into AI and machine learning. An employee who would only identify himself as Mr. Tanaka, because he wasn’t authorized to speak on the record, says the company will continue to focus on China. But, he adds, “we cannot rely on our past. As a company, we must adapt to new technology before we can create new technology. This will take time, but it’s necessary—the next generation of products have more functions, more connectivity, and more intelligence.”

A few years ago, in response to criticism from investor activist Daniel Loeb, who accused Fanuc of hoarding cash and investing in long-term growth to the detriment of annual returns, Yoshiharu held another of the company’s rare access sessions on the Oshino campus. Speaking with Japan’s largest daily business newspaper, the Nikkei, he addressed more directly than ever before the rising anxiety about robots taking jobs away from human workers.

After describing new “human-friendly robots” that can help workers lift heavy loads, he insisted that “robots are merely tools to make our lives better and easier. They reduce the time we must spend on routine tasks, giving us more time to focus on process control and other managerial duties. Robots will not replace us completely.”

His explanation was arguably less comforting for workers in other countries than for those in Japan, which is experiencing its worst labor shortage in decades and where worker-friendly labor laws make it difficult for companies to lay off employees for almost any reason, least of all so they can be replaced by robots. Japan also has a legacy of successfully balancing human and robotic labor. Toyota Motor Co., for example, uses hundreds of Robodrills to machine and drill parts, but the company says it has relied on robots for less than 8 percent of the work done on its global assembly lines in the past decade.

Factory automation, Mr. Tanaka says, clears a path for new ways of doing things even as it upends the old ways. “Any process which can be automated frees the human hands,” he says, “which in turn frees the human mind.”