Germany and Turkey have deep ties, with millions of ethnic Turks living in Germany, millions of Germans flocking to Turkey’s beaches and historic cities, and almost 7,000 German companies—from giants such as Deutsche Bank, Siemens, and Volkswagen to tiny importers of textiles and food—doing business there. Add it all up, and trade between the two tops $36 billion a year.

But an escalating war of words over democratic values has strained those ties. After a year and a half of tension, the relationship between the two NATO allies reached an apparent breaking point in late July after Turkey detained a group of human-rights activists, including Peter Steudtner, a German national. Chancellor Angela Merkel was uncharacteristically blunt in response, denouncing the move as “absolutely unjustified.” German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel, with Merkel’s blessing, announced a “reorientation” of relations between the countries, warning German companies about doing business in Turkey and cautioning German travelers about visiting. That prompted a denunciation from Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who called Germany’s actions “unforgivable” and suggested that some form of retaliation might be coming. With these accusations flying, it was revealed that Germany’s federal police had received a list of 678 German companies suspected by Turkey of supporting terrorism, which officials dismissed out of hand.

While relations between the two are arguably at their lowest point of the postwar era, both sides have a lot to lose by letting them deteriorate. Merkel needs Erdogan’s help to keep the flow of refugees into Germany in check, and the Turkish president relies on Germany, his country’s largest trading partner, for tourist visits and as a market for its exports.

Relations began fraying after Merkel helped broker a deal between Erdogan and the European Union last March, at the height of the migrant crisis that has roiled European politics, to control the flow of refugees from the Middle East into Germany. That accord has largely held—and with it, backing for Merkel’s party, which had been tested by widespread anti-immigrant sentiment.

Since then, Merkel has had to adopt a conciliatory posture toward Erdogan, even as the Turkish leader has cracked down on dissent, jailing more than 100,000 of his citizens following a failed coup last July. With a federal election just two months away, the German chancellor’s Christian Democratic Union—which leads rival Social Democrats by 18 points in the latest polls—can hardly risk the deal with Turkey falling apart. Merkel faced potential backlash at home last year when she allowed for the prosecution of a German satirist over a lewd poem about the Turkish president under an antiquated German law protecting foreign heads of state from libel. (The state prosecutor stopped the investigation on the grounds that the alleged crime couldn’t be proven “with the necessary certainty.”)

“It’s been a very fine balancing act for Merkel, and so far it has worked,” says Judy Dempsey, a senior fellow at Carnegie Europe, part of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “On the other hand, it’s given Erdogan more or less carte blanche to do whatever he likes. Erdogan may get a lot of points hitting Germany back in Turkey, but there’ll be a very high price to pay for both sides.”

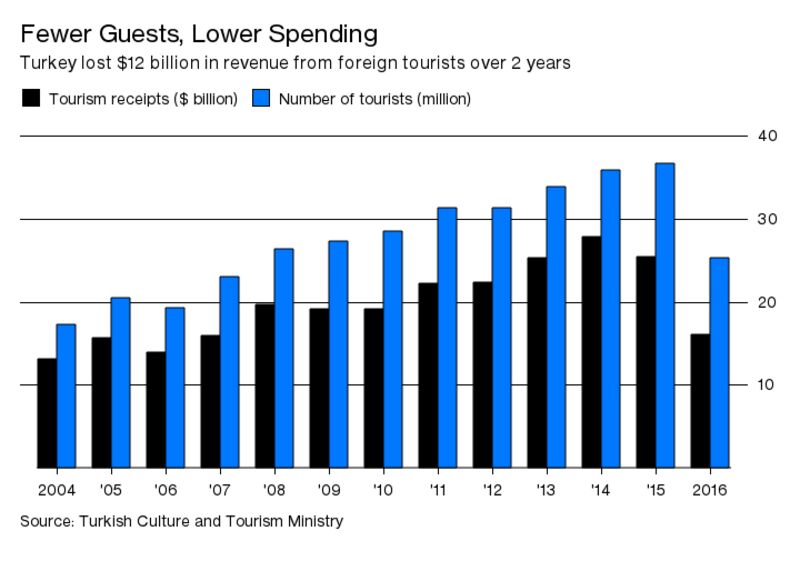

In exchange for accepting refugees, Turkey will receive a total of €6 billion ($7 billion) by 2018 from the EU, making it loath to drop its side of the bargain. What’s more, the number of foreign visitors to Turkey fell by more than 10 million last year; in the first five months of this year, visits by Germans, traditionally one of the biggest tourist groups visiting Turkey, were down 25 percent.

Turks make up Germany’s largest ethnic minority, and of the 3.5 million naturalized citizens and dual-visa holders living there, 1.3 million are allowed to cast ballots in Turkish elections. After Germany blocked Erdogan’s ministers from campaigning in the country for an April referendum transferring more power to the presidency (which the Turkish leader went on to win), Erdogan accused them of employing “Nazi practices.” A German parliamentary vote in June of last year recognized the killing of Armenians a century ago during the Ottoman Empire as genocide; that led Turkey to bar German lawmakers from visiting their country’s soldiers engaged in the fight against Islamic State stationed at a base in Turkey. Merkel then downplayed the significance of the genocide vote.

There are some signs Germany and Turkey are trying to cool the crisis in their relationship. With the jobs of thousands of Turkish workers at German companies on the line and perhaps seeking a way to back down from the latest round of rhetoric, Erdogan’s government on July 24 withdrew its list of supposed supporters of terrorism, calling it a “communication problem.” A spokesman for the German Interior Ministry acknowledged the clarification but stopped short of lifting the travel advisory.

“There is a critical public opinion here in Germany as regards policies toward Turkey, developments in Turkey, and above all, the reaction of the German government,” says Gülistan Gürbey, a political scientist at Berlin’s Free University who specializes in Turkish-EU relations. Erdogan, she says, has been testing his limits with Germany—and may finally have reached a limit.