At Bank of Taizhou Co., trainees are pushed to count money with lightning speed, toughened up by ex-instructors from the People’s Liberation Army and mobilized to go after delinquent borrowers with the subtlety of an infantry battalion.

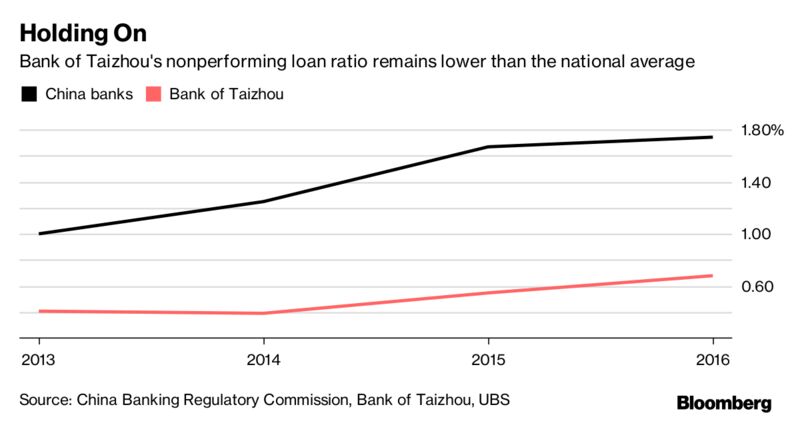

The boot camp ethos would seem laughably bizarre if it weren’t for this: Bank of Taizhou is being called China’s most profitable lender and has delivered industry-beating loan margins since at least 2013.

The little-known bank is achieving these results by employing a lending model from Germany to scrutinize its borrowers, the thousands of entrepreneurial industries ranging from small equipment makers to plastic molding companies in the southeastern coastal province of Zhejiang.

By forging a model for the rest of China, Bank of Taizhou’s success shows that it’s possible to lend to small businesses — a sector long neglected by banks that accounts for more than half of gross domestic product — and make good money doing it.

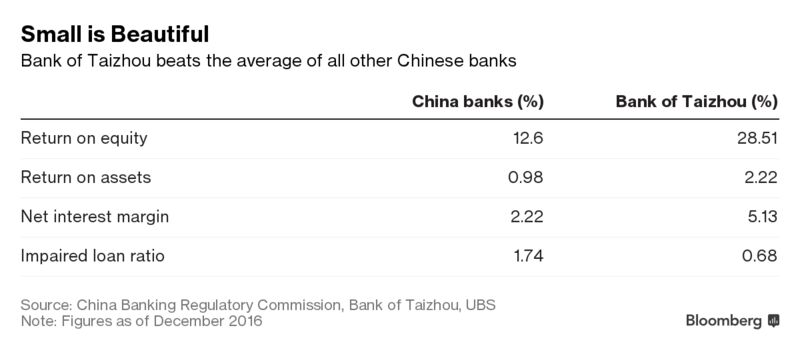

There’s not a lender in China that beats Bank of Taizhou for profitability and asset quality, UBS Group AG concluded after picking over the financial statements of 237 banks across the country.

“This bank just stuck out” on almost every metric, said Jason Bedford, the Hong Kong-based UBS analyst who led the study and plowed through the filings.

The risk-profiling system was brought in by a micro-finance expert from Germany, Joern Helms, who was hired as the bank’s first foreign recruit. Known as IPC lending after the German consulting firm that originated it and where Helms had worked previously, it’s being held up by the World Bank as a guide for small-business financing.

“I disagreed with the view that small businesses are difficult to assess and small businesses are risky,” said Helms, 44, who stepped down as a Bank of Taizhou vice president in 2014 after almost a decade with the bank and now serves as a Shanghai-based adviser to the company. “What we added was a systematic approach to measure repayment capacity.”

Big banks are reluctant to lend to small businesses, instead concentrating more of their lending on state-owned enterprises. Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd. extended 16 percent of its loans to small and micro businesses last year, a proportion unchanged from 2015.

Small-business lending is one part of China’s finance industry not expected to draw foreign interest, even as the government announced last week a plan to remove limits on ownership. Global banks in China are instead targeting large companies with cross-border businesses and wealthy individuals.

The government has been trying to free up more cash for banks to lend to businesses that typically find it difficult to get credit, and keep the transactions in the officially regulated system. Some of China’s smaller, regional banks are more engaged in shadow financing than traditional lending, according to an August report by UBS. Unregulated loans have bloated the shadow banking industry to an estimated 122.8 trillion yuan ($19 trillion), according to Nomura Holdings Inc.

Zhejiang, especially its city of Wenzhou, where Bank of Taizhou also has a branch, became notorious in 2011-2012 for its shadow banking crisis, when dozens of business owners went bankrupt or committed suicide after not being able to repay loans to underground lenders, causing the government to intervene to increase funding for small businesses. While borrowing from shadow lenders remains an option, “the good businesses don’t have to go there,” Helms said.

Bank of Taizhou, which makes average loans of about $50,000 and whose shareholders include Geely Automobile Holdings Ltd., is showing up China’s banking behemoths. Return on equity was 29 percent last year, more than double the typical 13 percent among peers. ICBC, the world’s largest lender, managed 15 percent.

“It works because they’re a local bank, they know what’s going on, and they have a lot of information about their customers,” said Oliver Rui, a professor at the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai.

To be sure, the labor-intensive nature of IPC lending swelled Bank of Taizhou’s cost-to-income ratio to 36 percent, compared with an industry average of 28 percent. Of the bank’s 10,000-strong workforce, some 4,000 are account managers.

“Our strength is that we really understand the small firms, and we can provide better services to them,” said Bank of Taizhou President Huang Junmin, 51, noting that once customers get too big, the bank asks them to turn to larger lenders.

The bank’s model, tailored to the local culture, may be tough to replicate in provinces with a less entrepreneurial culture, said James Stent, author of “China’s Banking Transformation: The Untold Story” and a former director at China Minsheng Banking Corp. and China Everbright Bank Co.

Account managers may have as many as 300 borrowers at a time and keep up a brisk pace on visits around Taizhou, whose streets bustle with trucks hauling components to assembly lines across town. Bank branches open as early as 7:30 a.m. and in the summer close at 7:30 p.m., unlike the typical 9-to-5 of rivals, so that businesses can access funds before and after the workday.

Managers not only handle banking needs, but can help them deal with parking tickets or even serve as a matchmaker, a tactic that “increases customer stickiness,” Huang said. “We have a unique business model. We make friends with our customers.”

One of them, the founder of sewing machine maker Feiyue Intelligence Technology, last year borrowed 500,000 yuan from Bank of Taizhou at an annual interest rate of 9.6 percent — more than double China’s benchmark rate of 4.35 percent — to start his business. Ruan Bochun, 40, said the bank’s representative has become a friend. On a recent visit they could be seen joking together like old pals.

“I can communicate with him easily, otherwise I wouldn’t borrow money from him,” Ruan said as he puffed a cigarette and drank tea beside hundreds of cardboard boxes and polystyrene shells.

There’s little tolerance at the bank for missed repayments. If there’s even a hint of them being late, teams mobilize to phone the client, visit the business, and contact the guarantor or other people the customer knows, Helms said. If that doesn’t work, the bank will go to court, even for the tiniest amount.

In the past, squads would roam an errant customer’s neighborhood wearing T-shirts emblazoned with “Risk-Fighting Unit” to shame the borrower into repaying, said Helms. The clear message: Pay your debts, and pay Bank of Taizhou before anyone else. With its reputation as a strict collector established, the bank no longer needs drastic tactics.

An ethos of discipline among employees is honed by military-style training unheard of among Western lenders. At Bank of Taizhou’s training facility, people hired to be account managers and bank tellers spend up to three months learning the job. Half boot camp, half university, trainees bunk down six to a room, practice customer service at mock branches and are taught to count cash fast.

To steel them for future assignments, instructors — who must have had five years’ experience in the PLA — make students run 10 laps around the campus twice a day and teach them how to stand to attention and salute.

“We need to make it clear it’s not a job in the office,” said Hu Xianpeng, a Bank of Taizhou senior economist in charge of the training program, dressed in Adidas exercise clothing at the facility.

The tough ethos extends to headquarters, where Chinese maxims hang on meeting room walls: “Eat bitter,” “Be honest,” “Innovate.”

Helms ate some bitter himself in Taizhou, 400 kilometers (250 miles) south of Shanghai, when he arrived in 2005 on contract from Frankfurt-based IPC GmbH. European essentials like milk were tough to find. But more importantly, he initially faced objections from some senior staff to his seniority. And he had to win over employees with his new lending model — through an interpreter as his Mandarin was inadequate and many staff spoke a local dialect.

“My greatest talent is my resistance to frustration,” said Helms, who stands 190 centimeters tall (6 feet 3 inches), dwarfing almost everyone in Taizhou, and sports short, dark-brown hair that’s starting to fleck with gray. “They are having me around to sometimes say no, to think differently, to be able to think out of the box and not be subject to the same mechanics that a Chinese employee in a Chinese bank is subject to.”

In IPC lending, salesmen ask a barrage questions to determine creditworthiness. Instead of collateral, borrowers suggest a guarantor who can vouch for them. Helms says many small businesses don’t have reliable records, so account executives might ask the same question in different ways: What’s your monthly income? Then later: What’s your annual income?

“They’re looking for a lie, an exaggeration or a misconception,” said Helms. “It doesn’t have to be 100 percent accurate. It just has to be close enough to make a judgment.”

Key figures might be checked with a relative or another employee. According to Helms, it’s hard for business owners to maintain a lie. And despite the need to grill borrowers, most small businesses repay their debts, he said.

“They don’t run away, they don’t do leverage, they just stay there,” Helms said. “It’s a low risk thing.”