-

Feminize Your Canon

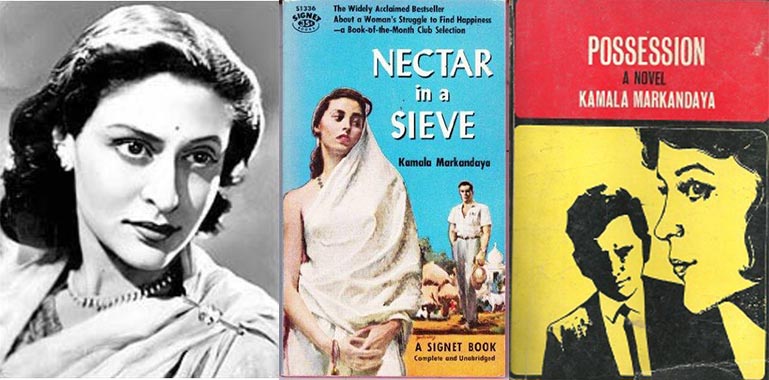

Feminize Your Canon: Kamala Markandaya

By Emma Garman

Our monthly column Feminize Your Canon explores the lives of underrated and underread female authors.

In 1956, the then-famous Indian novelist Kamala Markandaya was asked if she might set a book in England, where she lived with her British husband. “No,” she responded, “I don’t know England well enough, and don’t think a static society—that is to say a society which has solved its problems in a mild and satisfactory way—can prod me into writing about it. I regret to say I have to be infuriated about something before I write.” A decade and a half later Markandaya’s greater familiarity with English society, and its increasing volatility, resulted in her seventh novel, The Nowhere Man. Her favorite of her own works, it belongs alongside such classics of diaspora disenchantment fiction as Sam Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners, Andrea Levy’s Small Island, and Linda Grant’s The Clothes on Their Backs. Yet The Nowhere Man was all but ignored on its publication and, despite being reissued by Penguin India in 2012, remains little known today.

-

Feminize Your Canon

Feminize Your Canon: Violet Trefusis

By Emma GarmanOur monthly column Feminize Your Canon explores the lives of underrated and underread female authors.

“O darling, aren’t you glad you aren’t me?” wrote Violet Trefusis to her pined-for lover, Vita Sackville-West, in the summer of 1921. “It really is something to be thankful for.” On the face of it, Trefusis—née Keppel—didn’t deserve anyone’s pity. At twenty-seven, she was brilliant, beautiful, and privileged beyond compare. Both her grandfathers had titles: an earl on one side and a baronet on the other. She had grown up in various grand homes with frequent foreign trips, spoke French and Italian fluently, and planned to be a novelist. Influenced by Oscar Wilde and Christina Rossetti, she was an aesthete whose god was Beauty. “If ever I could make others feel the universe of blinding beauty that I almost see at times,” she wrote, “I should not have lived in vain.”

The only black mark on Trefusis’s illustrious background was the question mark over her father’s identity. As was then customary among the upper classes, her parents had an open relationship. All through Trefusis’s childhood her mother, Alice Keppel, was the mistress of Edward VII, whom the young Violet knew as Kingy. But he wasn’t her father: her birth predated the relationship, a fact that didn’t stop Trefusis dropping hints about her royal lineage. Nor was Alice’s complaisant husband, the Honorable George Keppel, the father. The likeliest contender was William Beckett, a banker and Conservative MP whose nose Trefusis apparently had. “Who was my father? A faun undoubtedly!” she joked to Sackville-West. “A faun who contracted a mésalliance with a witch.”

-

Feminize Your Canon

Feminize Your Canon: Rosario Castellanos

By Emma GarmanOur monthly column Feminize Your Canon explores the lives of underrated and underread female authors.

Solitude seeks fulfillment in my tears

and awaits me in the depths of every mirror

and closes the windows carefully

so the sky will not come in.

—Rosario Castellanos, excerpt from an early untitled poem.Images of literal and emotional solitude haunt the work of Rosario Castellanos, the visionary Mexican feminist, poet, novelist, and essayist. It’s a state she both cherished and mourned. From a young age, the act of writing was her bulwark against the pain of loneliness. “In order to feel ‘accompanied,’ ” she says in a newspaper column toward the end of her too-short life, “I almost never felt the need of the physical presence of another.” She adds, however, that “there comes a time when I have to admit that I am a totally helpless creature, and my eyes fill with tears thinking about the fact that I am orphaned and divorced.”

These words epitomize the prose style—vulnerable, revealing, self-searching—that for Castellanos was a conscious feminist act, a way of carving out a female space in public intellectual life. Among the literati of postwar Mexico, her unembarrassed confessionalism incurred derision. But rather than emulating the default male modes of writing, Castellanos critiqued them. She satirized the articles that offered sweeping pronouncements on Mexican politics and culture; she taught her students that Hemingway’s much-vaunted machismo was not a literary virtue; she took Graham Greene to task for what she viewed as his propagandism. In her own fiction, she foregrounded the perspectives and experiences of Mexican women who, whether white or indigenous, were otherwise denied a voice. And she engaged with the ideas of women writers from other nations, such as Simone de Beauvoir, Simone Weil, Gabriela Mistral, Emily Dickinson, and Virginia Woolf, whom she viewed as kindred spirits. “It’s not good enough to imitate the models proposed for us that are answers to circumstances other than our own,” a character says in Castellanos’s 1973 play, The Eternal Feminine. “It isn’t even enough to discover who we are. We have to invent ourselves.” Read More

-

Feminize Your Canon

Feminize Your Canon: Violette Leduc

By Emma GarmanOur monthly column Feminize Your Canon explores the lives of underrated and underread female authors. In the summer of 1956, Violette Leduc, the autofiction pioneer and protegée of Simone de Beauvoir, began inpatient psychiatric treatment. She was forty-nine and suicidal. Her first two novels, L’asphyxie (translated as In the Prison of Her Skin) and L’affamée (The starving woman), both published in the late forties, were read and admired by Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Cocteau, and Jean Genet. “She is an extraordinary woman,” Genet would tell people. “She is crazy, ugly, cheap, and poor, but she has a lot of talent.” Albert Camus, who had accepted L’asphyxie for his series at Éditions Gallimard, likewise considered Leduc a brilliant writer. But critics were underwhelmed, and the public all but ignored her work. “I don’t think of myself as not understood,” she writes. “I think of myself as nonexistent.”

In 1954, her third book, Ravages, which had taken six years to complete, was deemed too shocking to be published in its entirety. The male reading committee for Gallimard characterized the opening section, an autobiographical portrayal of the passionate romance between schoolgirls named Thérèse and Isabelle, as “enormously and specifically obscene” and liable to “call down the thunderbolts of the law.” Summarily excised, the section wouldn’t be published for another forty-five years. Yet Leduc’s dreamy, metaphor-burnished rendering of adolescent desire, which conveys as much emotional as physical sensation, is erotic but neither graphic nor coarse. “I was reciting my body upon hers,” Thérèse narrates, “bathing my belly in the lilies of her belly, finding my way inside a cloud. She skimmed my hips, she shot strange arrows.”

It’s difficult to imagine such lines corrupting twentieth-century sensibilities any more than, say, Joseph Kessel’s Belle de Jour (published by Gallimard in 1928) or Genet’s gay classic Lady of the Flowers (published by Gallimard in 1951, albeit with some of the more pornographic scenes cut). As the novelist and Leduc champion Deborah Levy has said, the publisher’s prudishness seemed to rest on the fact that Leduc’s narrative is driven by the female libido—almost unique in literature then and hardly more commonplace today. Read More

-

Feminize Your Canon

Feminize Your Canon: Dorothy West

By Emma GarmanOur monthly column Feminize Your Canon explores the lives of underrated and underread female authors. The career of the Harlem Renaissance writer Dorothy West featured one of the most remarkable second acts in literary history. Almost half a century after her trailblazing debut novel, The Living Is Easy (1948), West published her second novel, The Wedding (1995), at the age of eighty-seven. It received an ecstatic reaction. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, at the time an editor for Doubleday and a fellow resident of Martha’s Vineyard, had encouraged West to complete the long-gestated work, which West dedicates to the late Onassis. “Though there was never such a mismatched pair in appearance,” West writes, “we were perfect partners.” Set on the Vineyard on a single summer weekend, The Wedding is narrated by an irresistibly droll omniscient voice that veers across centuries to trace the knotty, reverberating heritage of an affluent African American family. An instant best seller, it was adapted for television by Oprah Winfrey. The ABC miniseries, starring Halle Berry, aired not long before West’s death at ninety-one. When asked what she wanted her legacy to be, she said: “That I hung in there. That I didn’t say, I can’t.”

In the decades between her two novels, West published short stories—she was one of the first black fiction writers to be published in the New York Daily News—and for many years, she wrote columns for the Vineyard Gazette. Yet her enormous early promise seemed destined to go unfulfilled. Her name was but a footnote to the Harlem Renaissance, of whose luminaries she was the longest living but, then and still, the least famous. One reason West gave for her long spell out of the limelight was that she felt alienated by the black militancy of the sixties. When watching television in that era, she said, “almost all of the black people I saw, I didn’t like what they were saying.” Though she was already working on The Wedding, she worried that its backdrop of privilege and its message of communality (“Color was a false distinction; love was not,” one central character muses) would go down poorly in an atmosphere abuzz with Malcolm X’s revolutionary separatist rhetoric. Read More

-

Feminize Your Canon

Feminize Your Canon: Olivia Manning

By Emma GarmanOur new monthly column, Feminize Your Canon, explores the lives of underrated and underread female authors. The British novelist Olivia Manning spent her dogged, embittered career longing, largely in vain, for literary glory and a secure place in the English canon. Reassurances from friends that talented writers were often rewarded by posterity cut no ice. “I don’t want fame when I’m dead,” she’d retort. “I want it now.” Yet even the modest ambition of a solo review in a Sunday newspaper proved elusive, a snub that especially chafed whenever her archnemesis, Iris Murdoch, released a new novel to lavish coverage in the broadsheets. Manning was baffled by the praise heaped on the younger writer, whose novels she derided as “intellectual exercises.” Her own drew directly from real events and aimed to be “pieces of life,” which she saw as the proper purpose of literature.

Given the strength of her “hungering and thirsting after fame,” to quote one exasperated friend, it’s possible that no amount of recognition would have satisfied the woman known as Olivia Moaning. The nickname was not unjustified, as secondhand book dealers knew. Once, at a charity sale, Manning came across her novel School for Love priced at twenty pence. “You’re giving that book away!” she complained. “It’s a first edition. It’s worth far more.” Another time, a signed copy of The Spoilt City, the second volume of her Balkan Trilogy, was for sale in a secondhand bookshop for fifty pence. Buying it herself, Manning remarked, “I bet Iris Murdoch’s first editions fetch more than that.” The bookseller replied, “Well, Iris Murdoch’s a famous author, isn’t she?” Read More